‘De lʼaventura qe avenc’ – The Adventure Pattern in Old French and Old Provençal Narrative of the 12th Century

Romance Philology, LMU Munich

Principal Investigator: Prof. Dr. Bernhard Teuber

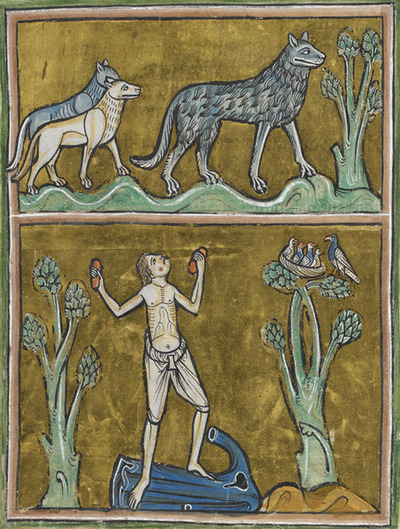

Rochester Bestiary, ca. 1230. © British Library Board (Royal MS 12 F. xiii, f. 29r).

The proposal investigates Old French and Old Provençal verse tales from the 12th and early 13th centuries as they appear in the Lais of Marie de France, in the five subsisting chivalry romances of Chrétien de Troyes, and in the Roman de Jaufré, the only Arthurian romance in Provençal Literature. We shall show that the emerging and successful pattern of the chivalric adventure (aventure) and its narrative realizations are right on the edge between early forms of adventure in the ancient novel and its avatars in early modern romances by Ariosto and Cervantes.

In Late Antiquity, novels stage the peripeties of undomesticated Fortune whose adversities the loving couple has to endure during the “time of adventure” (Bakhtin, Forms of Time), but nevertheless these adversities will be overcome thanks to benign Providence. In the Early Modern Era, however, Ariosto and Cervantes unveil the fictional or even parodistic character of their writings. In the Old French and Old Provençal texts, on the contrary, the happy ending of the adventures precisely oscillates between blind Contingency and supernatural or divine Providence. The medieval works are neither philosophical nor theological treatises; instead they intend to offer fictional entertainment which obviously differs from other literary genres of the same period. As they are based on the ‘matter of Brittany’ (matière de Bretagne), they appeal to the realm of Pre-Christian or even Non-Christian marvels which decisively determine the hero's actions. But there is no direct reference to the theological sphere of Christian religion. In our proposal, adventure will be analysed in its relation to a self-conscience that experiences this adventure.

Adventure simultaneously conveys two experiences to the knight and possibly also to his spouse: the proof of the radical imponderability of the “path of adventure” (Xuan, Subjekt der Herrschaft) as well as the satisfaction of having successfully overcome a perilous situation. The certainty of having overcome threatening perils and the telling of this story are closely related to each other, irrespective of whether it is the knight himself or his delegate who are summoned to tell the story. Hence the type of experience in which both the adventure and the adventure tale is grounded will have to be elucidated. Adventure is necessarily a retrospective category because adventure has always already occurred when we learn about it (“l’aventura qe avenc”, Jaufré). Therefore adventure can be considered as a characteristically medieval mold of subjectivation by means of which the self exposes itself to foreign agencies while moving along the “path of adventure” so as to achieve social status, gender identity and even political sovereignty.